Why Vertical Integration Often Tanks a Small Business

Vertical integration can be extremely fruitful - but only if you can bypass the hubris and egotism that often comes with the decision

When economies slow, when markets contract, and when uncertainty reigns, most companies tighten up and want to wait things out. That’s certainly a rational reaction, and there isn’t anything wrong with it if your goal is to just survive. Millions of leaders only want to keep the status quo, perhaps continue to grow at a slow, steady rate, and ensure profitability and cash flow remains strong. Don’t get me wrong – this is not only acceptable, but highly recommended for responsible business ownership.

However, if you have higher ambitions, perhaps to find ways to take over a specific market, or multiply your growth rate and profitability, you often have no choice but to consider expansions into other parts of your market stream, or even an acquisition to get you there quicker. The most common method of this is through what’s called horizontal integration. That is when you acquire someone at the same level of your industry in order to expand your own company.

Think of Coca-Cola and Pepsi. Those companies consistently stay in their lane – none of them are looking to open their own retail store, and none of them are collecting their own raw materials. Instead, they stick with manufacturing products and allowing their distributors to get those items in front of consumers. When they acquire other companies, it is almost always a competitor or a potential competitor whom they want to fold into their own operations and revenue streams. In recent years, Coca-Cola has bought Fairlife (a dairy company), Billson’s (an alcohol company), Costa Coffee, and others. Pepsi has acquired Poppi (a prebiotic soda brand), Rockstar (an energy drink company), Sabra (the hummus company), and others. While some of these companies may not be direct competitors with the parent company, they are all at the same level of the market: food/drink manufacturer. These two beverage behemoths continue to expand horizontally, while staying in their lane vertically.

Vertical integration, on the other hand, is when you expand upstream or downstream within the supply chain to have more control over it. One example is Live Nation merging with Ticketmaster. Both are in the same industry (live events), but Live Nation handles production of the events, while Ticketmaster handles the ticketing to the end users. They are in completely different parts of the entertainment industry, but their partnership gives the larger company much more control over the final product.

Apple is another great example of vertical integration. They control their own manufacturing, they control the software, they control the sales of its products through its distribution, and they sell an estimated 50 percent of their products to end users through its own retail stores and website (the remainder goes through other retail channels like Amazon, Best Buy, Target, etc).

Going back over a century, Carnegie Steel perfected the art of vertical integration: they controlled the raw materials, the supply, the logistics, the shipping, etc. This was one of the many reasons Andrew Carnegie became one of the richest people in human history.

Starbucks attempts to do the same thing: they own their coffee farms (the raw material), plus its own manufacturing and distribution to its own coffee shops, and then they sell the product directly to the end consumer (while also selling packaged versions in other companies’ retail stores).

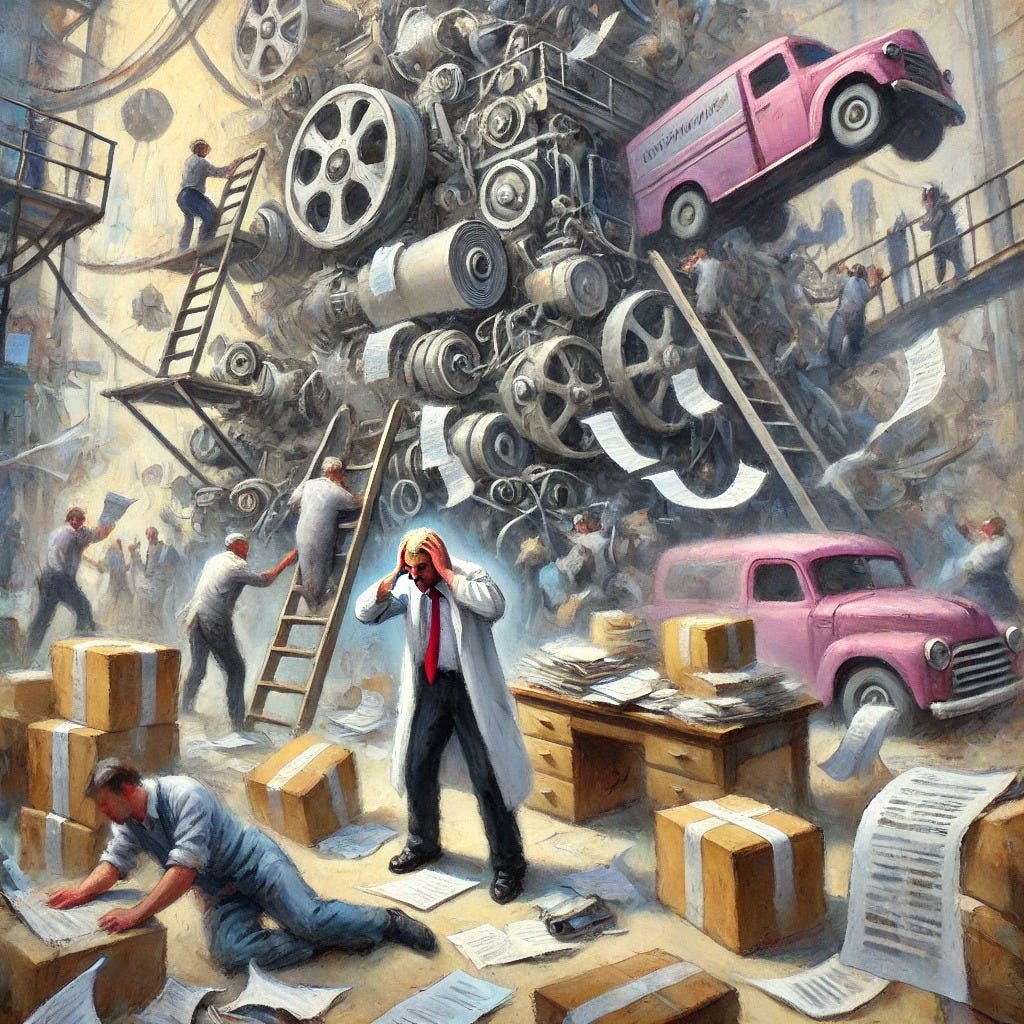

However, vertical integration is certainly not as easy as finding a company you want to buy and writing a big check. Vertical integration is actually one of the riskiest moves you can make in business, and more options are bound to be terrible for your company. Let’s say you’re a manufacturer and you’re unhappy with the fact that you have to sell a product at a large discount to a wholesaler in order to get access to a large network of retailers or consumers. Sure, by looking at the numbers, anyone capable of basic math can say, “Huh, if I can just skip that level of the supply chain and do it myself, I can make more money.” And if my grandmother had wheels, she’d be a bike.

If you’ve read anything on Main Street Mindset, or more accurately, if you’ve ever run a business of your own, you know that nothing comes easily in business. My actual grandmother used to say, “If business were easy, everyone would do it.” I think about that every time I run into a roadblock at work.1

If the aforementioned manufacturer thinks they can manage more parts of the supply chain, that’s great. But thinking you might be good at something, and more specifically, being blinded by potential riches, is not a substitute for doing your actual research. Let’s say you are the manufacturer and have a global network of customers. Do you actually understand the various markets your customers are selling in? Do you understand the differences between each continent, each country, each county? Do you know the laws and regulations of each of these places? Sure, you can learn, just like anyone can, but there’s a reason these companies exist and are successful in the first place. Don’t let yourself be blinded by ego or visions of grandeur. One of the best lessons I received in college was from my “Investments and Portfolios” professor, who answered another student’s question about trying to trade stocks based on something you think you know about the company’s future: “Why do you think you’re so much smarter than the entirety of the stock market?” or “What do you think you know that no one else in the world does?”

I often ask myself this question to humble myself when I think I’ve come up with a brilliant idea. If it’s so brilliant, why has no one else done it? Sometimes, there is a legitimate answer. Other times, it helps me ground myself into reality and really critique my own ideas.

In our current example, the question would be, “What do you know about wholesaling or retailing that you believe none of your customers already know?” Remember, we’re not talking about multi-billion acquisitions anymore, we’re talking about small businesses. To insert yourself into a different part of the supply chain without actually understanding what is involved reeks of hubris, and companies that think too highly of themselves usually find themselves in bankruptcy a short time thereafter.

I recently read a quote from Justin Simon, a portfolio manager at Jasper Capital Management, in discussing CVS’s recent (failed) acquisition of Aetna that beautifully illustrated the dangers of vertical integration. He said, “If you put a V-8 engine in your car, it doesn’t automatically make it a Ferrari.” That’s similar to a quote that used to hang over one of my employees’ desks that said, “Going to church doesn’t make you a Christian any more than standing in a garage makes you a car.” Simply inserting yourself into another part of the supply chain does not suddenly make it work. You need to do some serious soul-searching in order to determine if your brilliant idea actually has merit to it.

If you’re thinking of vertically integrating your business, I would ask yourself these questions, and really ponder on them over the course of some weeks (using “supplier” and “customer” as subs for the levels above and below you on the supply chain, wherever that may be):

Are my suppliers/customers really not doing a good job at handling their part of the supply chain?

If so, why are they having trouble doing so? Is it the economy? Is it the market? Is it the way we’re approaching the market? Is it the product? Is it their operations?

Is there something I can do differently at my level of the supply chain that would solve these problems for my supplier/customer?

What would I do differently than my supplier/customer that would improve that part of the supply chain? Is the idea realistic, achievable, and profitable?

Here’s a crucial piece of advice, which can be generalized to any business question, but specifically vertical integration: there is a huge difference between someone not doing the job properly, and someone simply doing the job differently than you would. Different is not necessarily wrong. It can be, certainly. But just because you don’t like the way someone is running their business doesn’t mean you can necessarily do it better.

And if, after really grilling yourself on these issues, you legitimately believe you can? Then go for it. Just remember that vertical integration carries a greater risk than perhaps any other strategic decision you will make in your company’s lifetime.

So, like, at least six times a day.