What I learned about leadership from Ed Snider

Years researching the longtime Philadelphia Flyers owner helped me become a better leader. He has lessons to teach everyone.

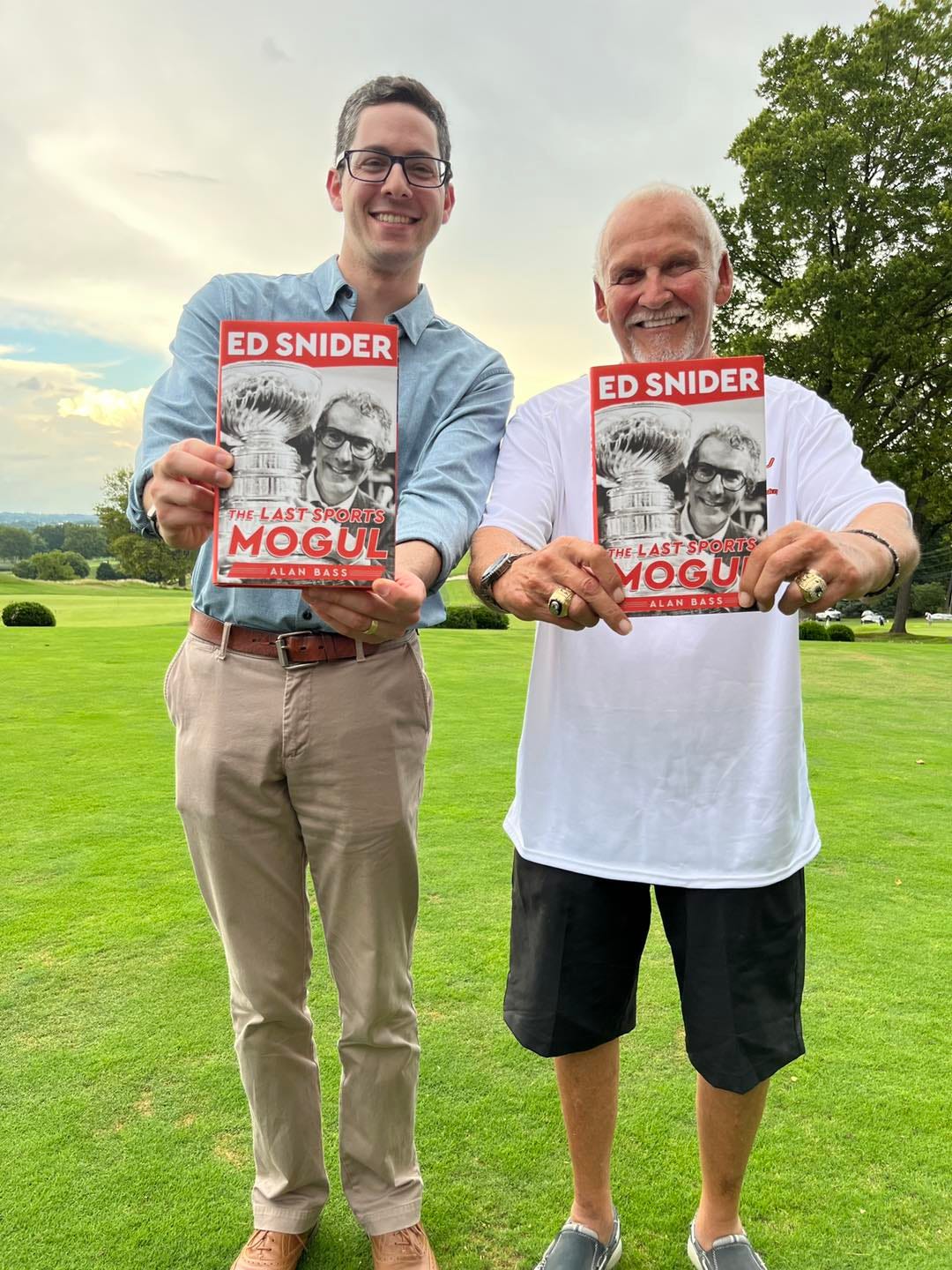

Shameless plug: I’ve published three books. I tell you this not because I want you to buy them (honestly, don’t buy either of the first two unless you’re a diehard hockey fan), but because I want to draw attention to my third and most recent book.

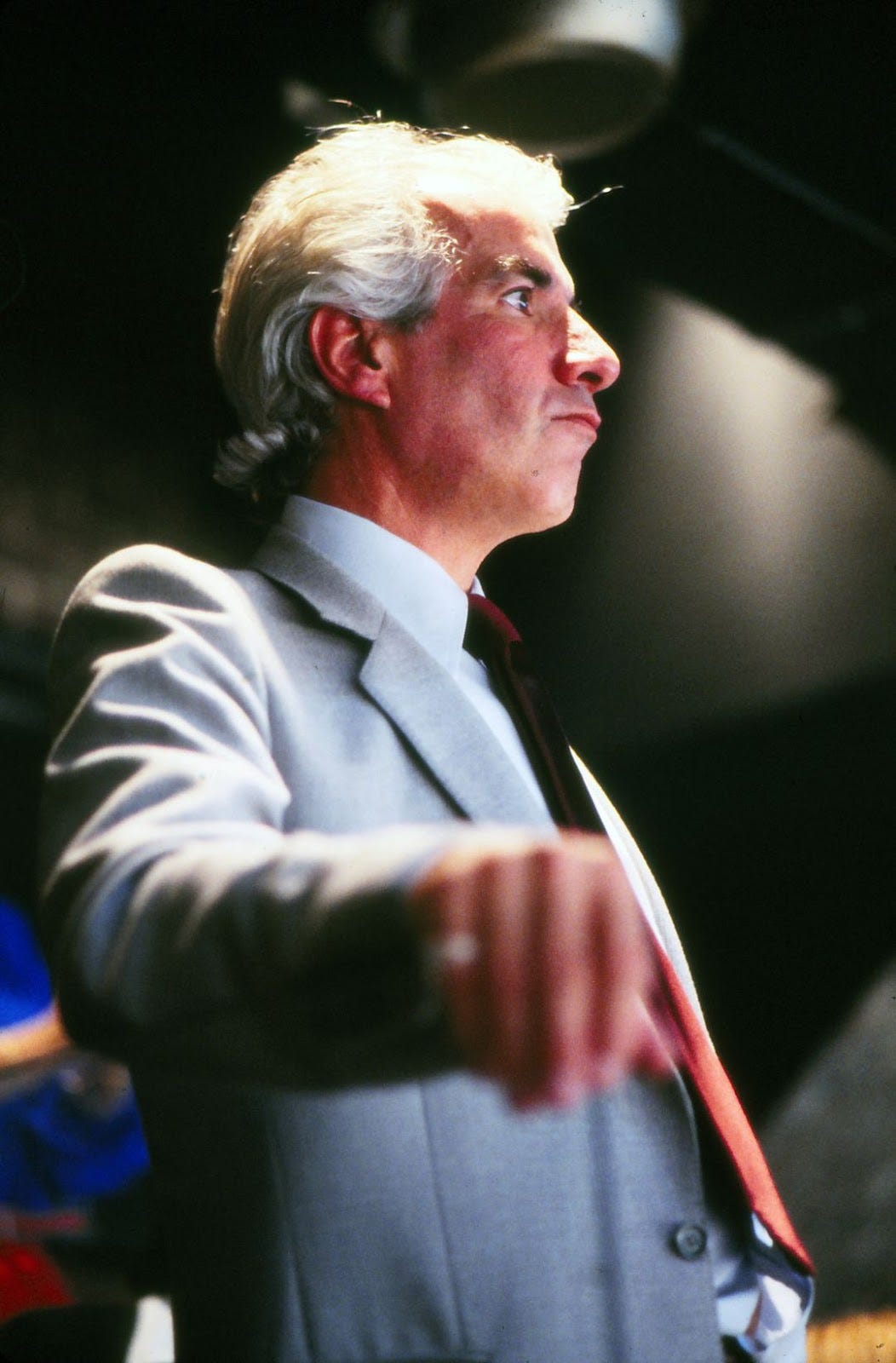

After decades following the Philadelphia Flyers hockey team, as a fan, as a writer, and then as a businessman, I wanted to write about the guy who ran the team for pretty much my entire life: Ed Snider. He’s got a phenomenal history that is a wonderful read for any businessperson or sports fan, which is why I embarked on writing his official biography.1

I spent multiple years researching, interviewing, and crafting his story, and when all was said and done, I was more proud of it than any endeavor I had previously attempted. People close to him, especially his family, were extraordinarily candid in sharing every bit about him they could, and it allowed me to weave a beautiful narrative about a complicated, yet successful man. But rather than biographize the man here, I want to instead make this specifically relevant to Main Street Mindset. Besides learning a great deal about Ed and his world, one of the most important takeaways for me was the ability to see and develop for myself some of the management tools he utilized for the better, while also staying away from some of the flaws he had in running a multi-billion-dollar company. While I certainly implore you to read the entire book and enjoy the story, I want to share with you the business tips that Ed taught me.

Hire the right people and let them do their jobs

This was Ed’s oft-repeated mantra that he tried his best to live by. I say tried, because Ed certainly had an aura around him of meddling and micromanaging that never quite went away, even after his death in 2016. Those close to him told me repeatedly that he never once told them what to do. But in my research, what was apparent to me was that Ed’s mantra was not about removing yourself completely from management. It was about knowing what was going on within his own company. He knew that even if he hired the best people, they still would need guidance and checking in from the one at the top. He wanted to be in the know – he would ask endless questions to make sure that they knew what they were doing.

For me, at the small business level, this has translated into a mantra of “trust your staff.” If you believe you’ve hired the right person to do a job, you need to make sure you give them the space and autonomy to do it. That doesn’t mean never check their work, and it doesn’t mean never correct them when they’ve made an error. What it means is that you need to be a guiding light for them so that they can complete the tasks on their own. Down the line, they will reward you by doing what needs to be done without you even telling them.

Don’t tell your employees what to do – help them figure it out on their own

This is a natural progression from the previous mantra, but I felt it was important enough to call out on its own. If an executive came to him with an idea for a new venture, he wouldn’t immediately say yes or no. Instead, he would grill them on every facet of the idea, which would eventually prove whether or not they had fully thought it through. More often than not, a stammer or hesitation in reply meant the idea wasn’t ready. But by forcing his staff to answer questions repeatedly, the person eventually discovered the answer themselves, to which Ed would say, “I knew you could do it.”

I use this strategy on a regular basis – to the point I actually implemented a policy in our office that no one can bring a problem to me unless they have a suggested solution. That doesn’t mean that solution is correct, but it at least starts the conversation so that we can find the best answer together. This has two benefits: from a cynical perspective, this strategy allows you to guide people to a solution you actually desire (if the situation calls for it), while making them believe it was their choice in the first place. From a developmental perspective, what this really accomplishes is making people think through a problem. If someone knows they can come to me and get a quick answer on any topic, there is never a need for them to think critically about any issue. That strategy would also beget laziness, which is a deep hole that is difficult to dig out of. Instead, you encourage a deeper understanding of the issues that may arise in your company, and inspire people to be a stronger part of it moving forward.

A fish stinks from the head

This is probably my favorite phrase that Ed used, because it’s both simple and humorous. One of Ed’s best qualities was that he always took responsibility for the things that happened in his organization, whether it was his fault or not (and whether he stated it publicly or not). He would remind people that if there is a problem in a company, more often than not you have to look to its head.

As a leader of nearly 50 employees, I think about this quote almost daily. There are a few benefits for living by this guideline. First, it helps humble you as a business owner. When you run a company, you can get used to people around you generally listening to whatever you say. But that’s not a good culture, and it’s not a good headspace to live in. By remembering that all of the faults in the building reflect on the company, and thereby my leadership, it keeps me grounded and in tune with everything that is going on.

Second, and more crucially, taking responsibility is one of the most important acts a leader can do, in any industry. When the people that work for you see you acknowledge error, even when it wasn’t technically your fault, it makes them respect you more as a leader and makes them proud to work for a company that is always striving to improve. It also shows them that there is nothing inherently wrong with mistakes – so long as you own up to them and fix them.

Anyone can make money by raising ticket prices. Let’s see you do it with what you got.

This one doesn’t directly relate to most small businesses, but hear me out. Ed said this to his general manager when he was asked why the Flyers ticket prices ranked in the bottom third of the league, despite selling out almost every game. Ed knew that supply and demand technically allowed him to jack up prices during the team’s winning periods, but he also knew he was more likely to alienate his customers in the long run by doing so.

Now, while every business has some semblance of supply and demand, the business we’re in generally doesn’t price goods that way. Prices increase over time, of course, but they do not go up and down throughout each year. We often joke in our office that if we could increase the price of toys during the holiday season, we would all make a lot more money. But in reality, we know that would be a terrible way to do business and only create warranted ire from consumers and retailers.

Think about the travel industry. Airlines know that you have almost no other option when you need to go somewhere. Prices skyrocket when there is heavy demand, making it almost unaffordable for many people to travel. That doesn’t necessarily mean people will stop flying – it just makes them have incredible negative emotions toward the airline industry.2 The same can be said about almost anyone else in the service industry (e.g. contractors, repairmen, etc). You don’t want to run your business in a way that forces people to interact with you against their will. You want them to choose to patronize your company.

This mantra doesn’t mean “don’t ever raise prices.” It means don’t utilize price increases as your primary method for increasing your revenue and profit. What started as a hockey team in 1967 was a huge entertainment conglomerate by the time Ed passed 50 years later. The various arms of his business helped ensure that the hockey team did not need to be consistently profitable for the company to succeed. Ed was a master at finding new avenues for which to make money in his business. What new revenue streams or efficiencies can you find in your company to benefit your customers?

The rest

Without going into too many details, Ed also had a lot of negative leadership qualities: he was absent from his family in his early years and often alienated those close to him with his temper. He was often impulsive, leading a select few to have to physically calm him down at times. He was often too trusting of some of his top executives, occasionally leading to illegal and unseemly activity that ended up biting him in the rear once he discovered it.

With any figure you may look up to, whether they are in the public eye, or even just someone close to you that you admire, there are always positive and negative qualities. The key is to pick out the leadership lessons that work for you and improve upon your abilities, while avoiding those which you know can hurt you. As small businesses, we don’t usually have the luxury of expanding in the way that Ed did. But that doesn’t mean we can’t utilize some of his mantras to become better leaders in our own right.

Let me know your thoughts about Ed’s mantras and how someone you admire helped you become a better leader.

Okay, now I want you to buy the book. Buy three, in fact.

Seriously, do you know anyone who says, “Man, I just LOVE [insert name] Airlines. What great people they all are. They make me smile every time I go to the airport. Especially those executives who run the joint!”

Alan...bravo my friend. I knew Ed for many years and you are right on.

Be well...Happy New Year & best to Emily.