The Myth of the “Three-Generation” Rule

There is a popular statistic that most family businesses don’t last through the third generation. Its main point is misleading.

Most people in family business (and many of those in big business) have heard that the majority of family businesses don’t last to the third generation. Indeed, statistics show that just 30 percent of family businesses succeed to the third generation, 10 to 15 percent make it past the third, and three to five percent make it through the fourth generation. Family businesses, the story goes, are fickle, with most of them failing in the long run.

These statistics, for decades, have been used to show how risky family businesses can be. It’s spoken about any time there is a succession between generations – “Jim was an unbelievable leader, there’s no way his son/daughter/nephew/niece can live up to that.” And anytime a family business does go under after a succession, people point out how the odds were against the young gun in the first place.

“That next generation just doesn’t have the same work ethic,” some will say. “They don’t understand what went into building the business, so there was no way they could properly appreciate what was required to keep it going.” Have you heard this before? As someone who is currently a third-generation family business owner, I certainly have, and not just about myself.

The problem is, while the data is technically correct, the interpretation is wildly inaccurate. As someone who loves to use numbers to support or retort or a claim, I know firsthand how data can be manipulated to achieve a desired conclusion. The book “How to Lie With Statistics” isn’t just a clickbait-y title – it’s an accurate statement about how we can so easily be thrown by a few truthful figures.

The data is true: family businesses have a high failure rate, especially as the years progress. What the reporting conveniently omits, however, is that all businesses have a high failure rate.

There are an inordinate number of data points on business failure rates as a whole, and while they vary somewhat, they are all in the same ballpark – so you’ll excuse me if some of the below seems a few percentage points off of what you find in your own research.

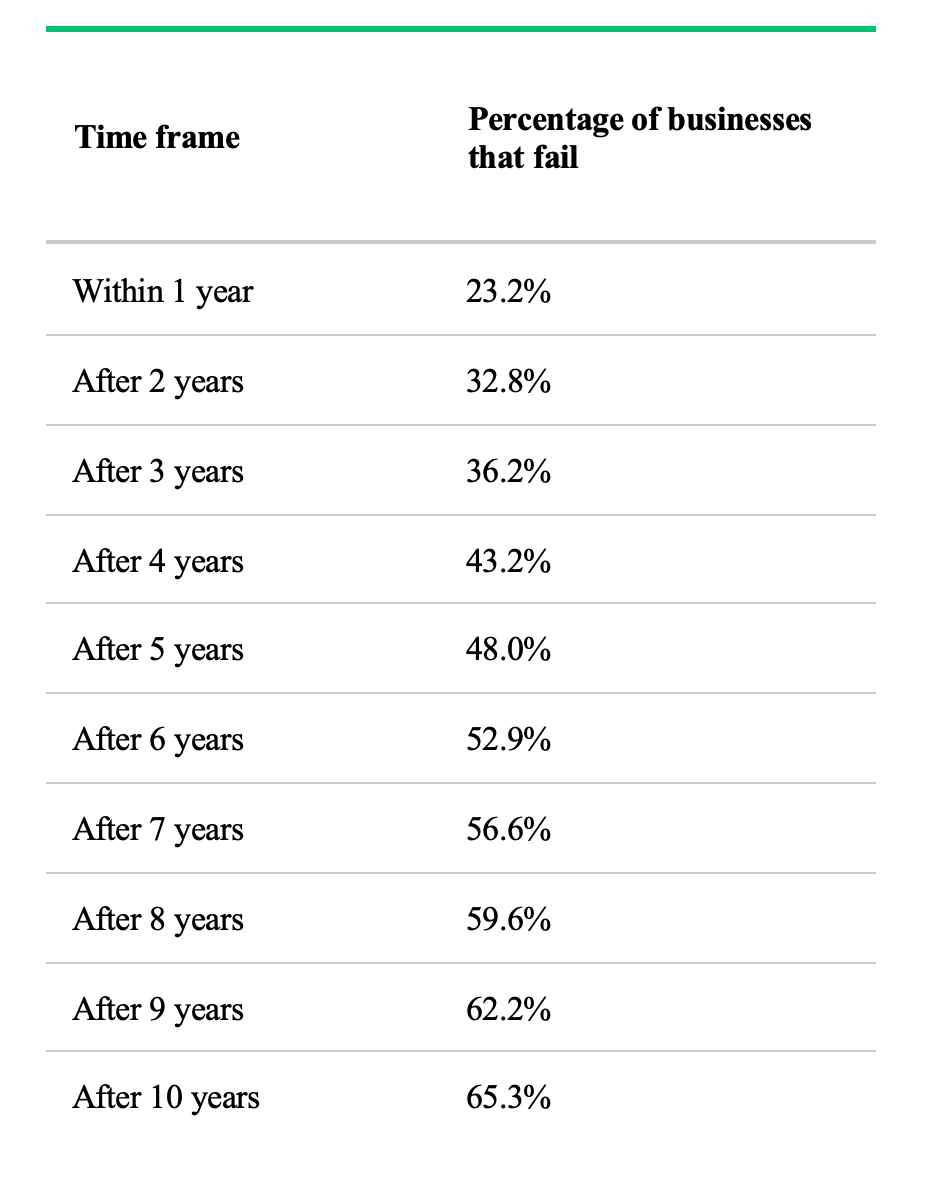

According to the New York Times, the average lifespan of any small business is 8.5 years – and since small businesses make up 99 percent of all incorporated companies in the United States, you can pretty much generalize that number to all businesses. According to Entrepreneur.com, a new business experiences an average annual growth rate of just two to three percent in its first five years. According to Smallbizgenius.net, just 40 percent of small businesses are profitable. In an examination of companies of all sizes started in 2006, 78.3 percent made it to the end of their first year. Just 32.8 percent made it to the end of their tenth year. Take a look at this chart from LendingTree.com, showing the failure rate by year for a business of any size:

You see that number at the bottom? That’s not even a full generation, and yet businesses as a whole are failing at a higher rate in ten years than the average family business does in two full generations. If I were someone who likes to lie with statistics1, I would say the data suggests that family businesses are actually safer than any other kind.

But I’m not actually ready to go there just yet. As we already see, data can be misleading.

As a whole, it’s fairly obvious that owning a business is difficult. To make one last, you need all sorts of intelligence, support, and most importantly, luck. Sometimes you can make your own luck, but even the best businessperson may run into a failure through no fault of their own. And we all know at least one entrepreneur who doesn’t remotely deserve the success they’ve had.

Business ownership is difficult, and it’s getting harder. A study of 25,000 publicly traded companies from 1950 to 2009 showed that the average lifespan of a current business is 15 years.

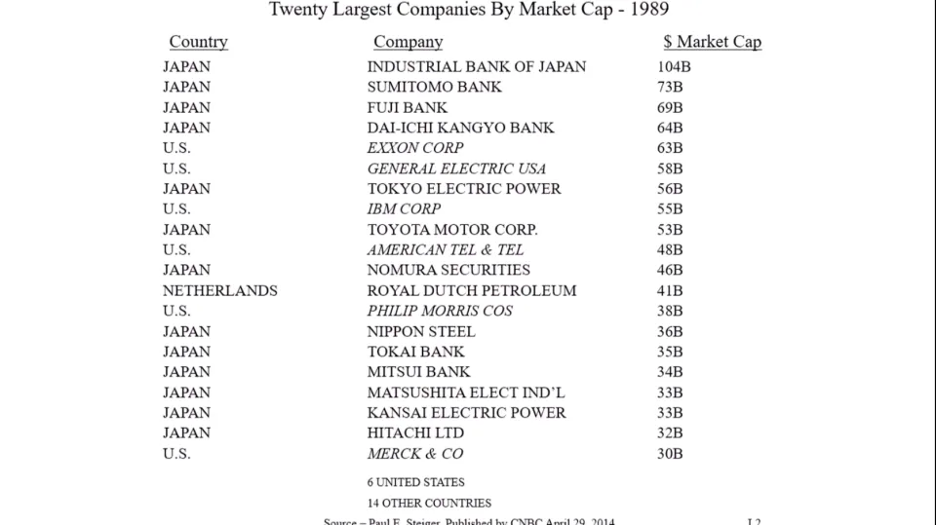

In fact, one of the brilliant minds of our era, Warren Buffett, showcased the fickleness of business perfectly during Berkshire Hathaway’s 2021 annual shareholders’ meeting. He was talking down those who confidently state that they can predict the market, or that they know what the market will look like in 20 years. In response, Buffett popped up the below slide, showing the 20 largest companies from 1989 by market cap:

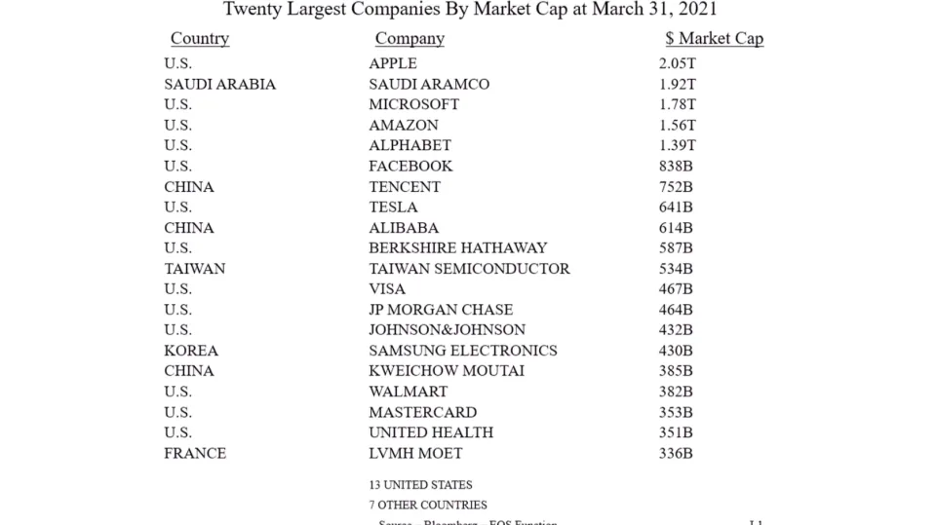

How many of those company names do you even recognize, let alone do you think are still in the top 20 over 20 years later? Not to worry, Buffett showed his work:

Not a single company from the 1989 list was still there in 2021. In fact, only 12 of those 20 from the first chart still exist in the same form today. These are companies that were the giants of the global market – not even small businesses!

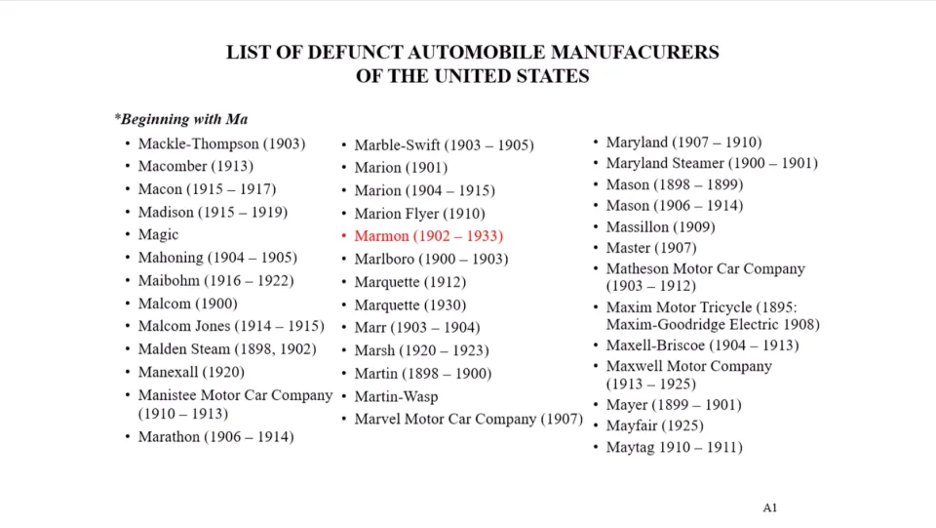

To drive his point home, Buffett showed a slide listing a collection of defunct U.S. auto manufacturers:

That’s 38 auto companies, just in the “Ma”-s, that went broke in the early 20th century. And if you look at a list of the largest U.S. companies in 1967, it’s riddled with companies that either didn’t last or have shrunk dramatically in size: Kodak, Sears-Roebuck, Polaroid, International Nickel, Westinghouse Electric, Sperry Rand – the list goes on and on.

Buffet’s point was the same point we’re talking about here: companies, on average, fail. It has nothing to do with small, large, or family. It’s just that sometimes, they don’t last, for a multitude of reasons.2

But let’s return to our original care: family business. One of the most staggering facts that I learned recently was that 13 percent of active family businesses are over 100 years old. Over 74 percent of active family businesses have been in operation for more than 30 years. This data is obviously skewed by the fact that we’re counting only active companies, not any of the ones that have failed over the years – but it still rejects the thesis that family businesses are more likely to fail than any other kind.

Family businesses have their own challenges, without a doubt. As a local trucking magnate recently said, “In a family business, there’s two businesses: the business of the business and the business of the family. If you don’t pay attention to both, you lose both.” What the failures amount to, which are not unique to family businesses, is succession. Family business succession can be easier than other businesses because there usually are only a few choices for the next leader, and they’ve often been trained their entire lives for it. The downside, of course, is that a simple family rift can take down the entire company at any time.

Non-family businesses don’t have that downside, but they struggle with succession just like any other company. Look at Starbucks, one of the most successful companies of the last generation: founder Howard Schultz has returned to the CEO’s chair what seems like 43 times because the company keeps struggling to find a suitable replacement. Bob Iger had to return to Disney’s corner office because the board’s attempt to succeed him failed miserably.3 The cherry picking of data specifically on family businesses is useful only to support the misguided thesis that somehow family businesses are riskier than any other kind.

The further good news is this: 91 percent of consumers prefer to support small businesses, and a larger number prefer to support family businesses. Don’t listen to the trite statements about the risks of family business. What the data truly shows is that all of us in small or family businesses, in actuality, have a leg up on any other company trying to survive.

Depends on the situation

Pop quiz: which state has the highest and lowest first-year business failure rate? Washington has the highest failure rate. Bet you didn’t think California had the lowest.

Although there is a messy story behind that failure, potentially pointing a hefty amount of blame at Iger himself