The Magic of the .300 Hitter: Why We Obsess Over Round Numbers

It’s human nature to prefer a round number. How can you use that to your benefit to find hidden value for your business?

Pricing tricks have been utilized in retail for decades. Marketers long ago discovered the magic behind pricing something at 99 cents instead of rounding up to the nearest dollar. Intuitively, we all know that something priced at $9.99 is the same cost as $10.00. If we all know this, though, why do retailers keep doing it?

Well, the simple answer is that it works. Despite our better judgment, our subconscious, irrational brains still want to see the smaller number. Our brain loves impulsive behavior and snap judgments, and it certainly loves seeing a small number on the left side of a price. This has been referred to as “left-digit bias.” It is the tendency of people to prefer the lowest possible number in the left-digit when looking at the cost of an item or service.

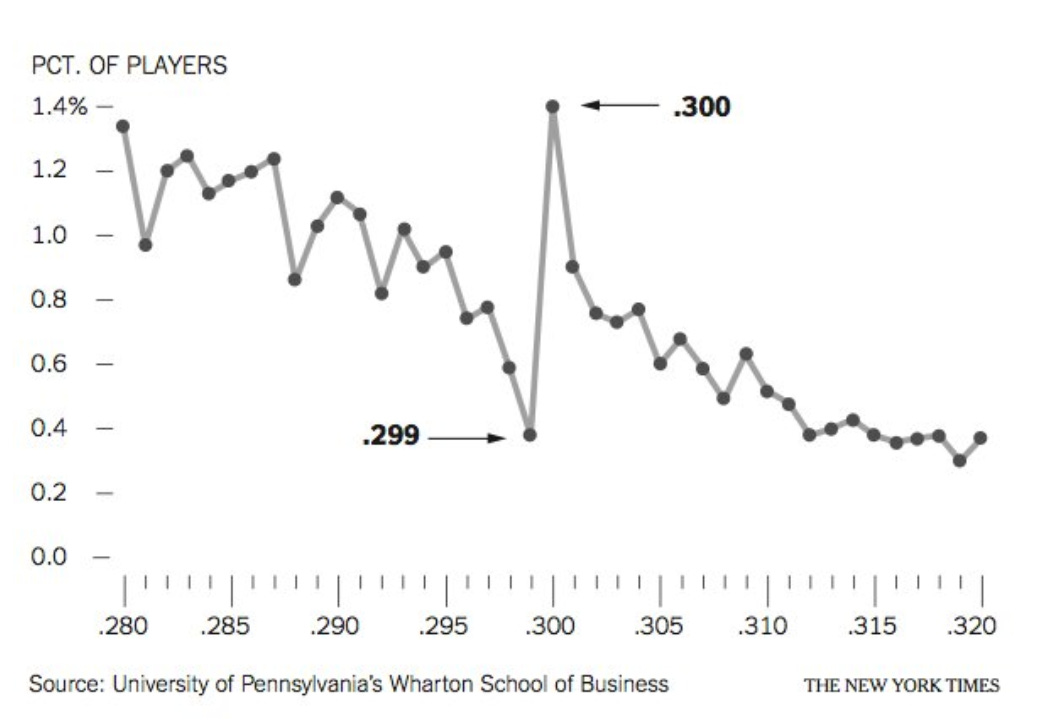

The “round number bias,” on the other hand, is the opposite: the preference, in certain scenarios, of people to prefer the round number to something just below. In their fascinating book, Scorecasting, Tobias Moskowitz and Jon Wertheim write about the round-number bias with regards to sports. When their book was published in 2012, they discussed some data that is almost unbelievable. A magic number for a baseball hitter is .300 – meaning they get a hit (or a double, triple, or home run) 30 percent of the time. That’s a historically large number: only the best of the best can hit the ball that efficiently over the course of a 162-game season. The authors realized, though, that while .300 hitters are rare, what’s even rarer are .299 hitters.

If a player was hitting .299 going into the last game of the season, they always attempted to get a hit – many struck out and had their average drop a point, while others got that hit, raised their average to .300, and were promptly removed from the game to secure their final stat line. What was mind-blowing is that, in pursuing this line of questioning, the authors found that in the over 100 years that baseball has existed, there has never been a batter who, when sitting at a .299 average on the last day of the season, walked in their last at bat of the season. Why? Because if you walk, your average is not affected at all. It’s as if the at-bat never occurred. And no one wants to be the person who nearly hit .300. The value of being a .300 hitter, both financially and historically, is immense.

But again, just like with pricing in a supermarket, is there really a difference between a .299 hitter and a .300 hitter? Of course not. They are nearly identical, statistically. Yet, the idea of being just below the round number makes athletes behave more irrationally in order to attain that pointless goal.

There are tons of examples of these statistical mountaintops in sports: 50 goals in hockey, 1,000 rushing yards in football, the 40-40 club in baseball, triple-doubles in basketball – the list goes on and on. But again, is someone who scored 49 goals in the NHL less valuable than someone who scored 50? Is an NFL running back not worth it if they only got 999 rushing yards one season? The value is the same. The only difference is your perception of the value.

This happens all the time outside of sports as well. Studies show that a high school senior is more likely to retake the SATs if their score ends in “-90”. Meaning someone who got 1200 is likely going to be happier with their score than someone who got 1490. The 1490 student is “oh so close” to 1500. The 1200 student is filled with relief that their score was above that nice, round, threshold.

The value of a car drops significantly at 100,000 miles. But is it any older than a car with 99,000 miles on it? The 99,000-mile car is being overvalued, and the 100,000-mile car is being undervalued. The same thing happens in the stock market: many traders place limit orders at round numbers (e.g. $10.00 per share), which creates a liquidity pocket that smarter, algorithmic traders can use to exploit, knowing that there will be a batch of purchases or sales at certain thresholds. It happens in medicine, as well: patients who just turned 80 were 25 percent less likely to get a coronary bypass than those who were just a few weeks shy of 80. A few weeks difference in age is irrelevant, yet even doctors acted irrationally when it comes to a round number.

I distinctly remember, years ago, when shopping for my wife’s engagement ring, learning that a 1.00-carat diamond cost significantly more than a 0.99-carat diamond. I don’t remember the actual numbers, but let’s say the difference between 0.98 and 0.99 was tens of dollars – the difference between 0.99 and 1.00 was closer to a thousand. And as an analytical, math-loving adult, I did what any rational man would do – I bought the 1.00-carat ring because I was not going to live with that risk for the rest of my married life.1

You see what I mean, though? Even when we know the facts, and know that we are acting irrationally, we still can’t help ourselves. If you look deep enough, all of you will likely find examples of this in your own lives each week.

The question, as it always is, is how can we use this natural human bias to our benefit as business leaders? For one, you certainly are stuck pricing things at “-.99” for the rest of your days. Even once the penny is eliminated from circulation, the left-digit bias will still exist, thanks to electronic payments (and stores inevitably rounding up during cash payments).

But on the other side, if you know what types of assets are overvalued, that means you also know what is undervalued. For example, if you’re hiring someone for your business, and the market maintains that this position should require ten years of experience, don’t stick to your guns too hard. The person with nine years of experience is likely just as capable, but probably will not be heavily recruited by others in your industry. Not only are you likely getting someone that costs less, but you will also get someone who is more devoted to your willingness to give them a chance. If you’re hiring at a place that requires a certain GPA, know that 3.0 students are overvalued and 2.9 students are undervalued. Go for the person who gives you the same performance but costs you less.

The same thing with asset purchases. If you’re looking to buy something for your business – let’s say a new printer – don’t be fooled by the round number. If Printer A advertises itself as being able to print 50 pages per minute, and Printer B advertises as 48 pages per minute, Printer B is likely significantly cheaper, but will achieve almost identical performance.

Lastly, if you set goals for yourself as a company, don’t be so blinded by the round number that you act irrationally in order to attain it. If you set a sales goal of $10,000 per month, and you’re on pace to finish at $9,500, it’s more damaging to do something stupid to get that last $500 than it is to simply say, “Ah, we were close. Let’s see what we can improve next month to finally cross that threshold.”

Our brains are wired to see patterns and desire round numbers. Put more simply, our brains are wired to act irrationally. Unlike most biases, simply being aware of the round number bias’s existence doesn’t help you overcome it. More likely, you’ll need to actually talk yourself off a ledge – do I really need the truck that has 49,900 miles? Or can I save a few thousand dollars and get the one with 51,000 miles on it?

By focusing on the implicit value of a product, service, or a person, instead of looking at a number and jumping to judgment, we can avoid making costly mistakes and overpaying for things that, at the end of the day, would not give us any additional benefit.

I’ll be frugal on other purchases, thank you very much.