Import Tariffs Have Had a Long and Inconsistent History

Now that both parties seem to agree on expanding them, though, do you know what effect it will have on your business?

One of the most-written about policies during the Trump and Biden administrations has been import tariffs. Former President Trump made no secret about his desire to start (or threaten to start) a trade war, increasing tariffs on many imports, specifically from China. Even though Democrats roared with disapproval at the time, President Biden did not undo any of those tariffs when he went into office – in fact, he expanded upon them by increasing his predecessor’s tariff on Chinese steel, aluminum, and medical equipment, and doubled and tripled tariffs on Chinese-made solar cells and lithium-ion electric vehicle batteries, respectively.

Now, amidst a heated election campaign, one side is threatening to implement a tariff on all global imports, while the other side has been conspicuously quiet about their trade policies. This has led to a combination of gloating and panic, depending on which side of the political aisle you are on. The problem is, most people writing about it have never paid an import tariff or tried to clear anything through U.S. Customs.

Don’t worry, we’re not going into politics here – but I do want to be sure that everyone understands exactly what import tariffs are, why they exist, and how they are enforced. Without that knowledge, no one can have a reasonable opinion on what trade policy we should pursue as a country moving forward.

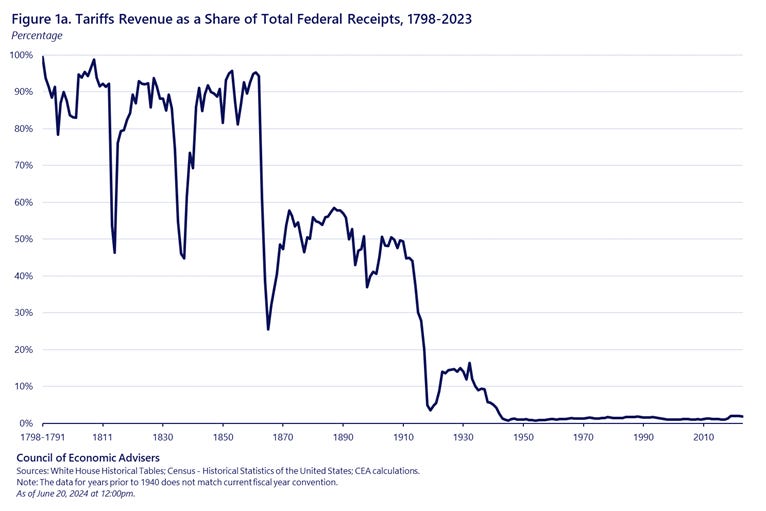

Tariffs have been a bedrock of this country since the very beginning. The Constitution specifically allows for the federal collection of “taxes, duties, imposts, and excises.” In fact, with no provision in our original governing document to levy a federal income tax, the choice for funding the government at the time was either taxing domestic production or taxing international trade. Tariffs would prove to be the most efficient way that the government could fund itself, especially since they wanted their young republic to grow.

Interestingly enough, the second law signed in the history of this country was the Tariff Act of 1789, in which George Washington’s signature established a five percent tariff on all imports. A couple years later, Alexander Hamilton presented Congress with his “Report on the Subject of Manufactures,” where he argued that tariffs would protect new American industry, support the domestic production of goods, and raise revenue for the government.

These tariff laws eventually led to the creation of the New York Custom House, which was actually the largest federal office in the nation for decades. With the majority of imports coming into New York at the time, the person running the Custom House had immense power – and also the ability to legally pocket a cut of all fines and forfeitures levied by customs inspectors.1 The Custom House was notoriously corrupt, as jobs would be given to political supporters that could be tapped for campaign contributions. In fact, Chester Arthur held that position under President Grant starting in 1871,2 eventually leading him to move up the chain to Vice President and then President.3

Fast forward to the 1910s, and the tariff rate had grown precipitously. Before the Civil War, average rates occasionally rose as high as 60 percent. During the war, they reached levels close to 50 percent. From 1871 to 1913, the average tariff rate never fell below 38 percent. But in 1913, tariff rates suddenly started to fall. Up until this time, tariffs accounted for about 95 percent of federal revenue. What changed?

Why, the 16th Amendment, which allowed the government to finally begin collecting a federal income tax. And as federal income tax rates rose over the years, tariff rates fell in an almost perfect negative correlation (ignore that bump in the 1930s for a moment – we’ll get to that). The government found a new way to generate revenue, making the tariff less important.

Let’s jump to the discussion of who “pays” for tariffs. One of the lines that has come out in the last few years is that the exporting country “pays” for tariffs. In this example, a tariff on Chinese goods would be paid for by China. Anyone who has ever done a lick of research knows that this is as untrue as could be. Tariffs are an import tax, known as a “duty”, on incoming goods. The person or company importing those goods is responsible for paying that tariff to the United States government. The only way a tariff hurts the exporting country is if the increase in U.S. consumer price causes demand to drop, thereby decreasing production at the manufacturer level back in the original country. But this usually doesn’t happen unless there’s a viable replacement option stateside (and if there was, more often than not they wouldn’t be buying it abroad).

Indulge me for a minute to explain how the customs clearing process works. Historically, tariffs have been the easiest taxes to collect. The process should hypothetically be efficient and simplistic, since imports aren’t released until the tariff is paid, which makes it a bit difficult to evade those costs. The way it’s supposed to work is that a shipment arrives into the country, CBP inspects the documentation, determines what the product is (using what’s called an HS Code), either via the documentation, by asking the importer, or physically inspecting the goods. They then apply the tariff, as well as other charges related to the process, receive payment, then release the goods to be delivered to the importer.

In reality, it more often than not happens like this: a shipment arrives in port. It sits there for two weeks before anyone realizes it’s there. They clear it without asking questions, under an HS code that isn’t even close, without ever reaching out – and of course, that incorrect code is usually classified under a much higher tariff rate. When you contact them to make an adjustment (which is extremely difficult once the paperwork has been filed with the government), the conversation usually proceeds as such:

“You cleared it under the wrong HS code.”

“We couldn’t tell what it was.”

“It was listed on the documents, along with the exact HS code that applies to the product.”

“Well we sent it for a customs exam. That’ll be $3,000 extra.”

“Why didn’t you just contact us to confirm what it was?”

“We couldn’t get in touch with you.”

“My email address and phone number are on the invoice.”

“We don’t have email or phones.”

Okay, that last quote may be a slight exaggeration, but you get the point. It’s a pretty messy process nowadays, even though technology should make this all much easier. Regardless, tariffs today make up less than two percent of total federal tax revenue. Which means that any adjustment in tariff policies is not revenue-related, but politically-motivated. And while I try not to get involved in politics, at least publicly, inevitably business decisions and politics will mix a bit.

Despite public rhetoric, trade wars are not “easy to win”, nor are they beneficial to anyone. Remember that bump in the chart that you were supposed to be ignoring? Well, stop ignoring it now! In 1929, the Smoot-Hawley Act was passed, which skyrocketed tariffs on all imports, immediately started a trade war with the rest of the world, most of whom implemented retaliatory measures. World trade dropped by two-thirds over the next few years, leading to countries isolating themselves from each other, as well as bank failures and economic turmoil. Some historians even argue that this isolationism, stemming from the economic issues following Smoot-Hawley, led to the rise in extremist ideologies of 1930s Europe.

This doesn’t mean import tariffs don’t have a place in our modern economy. But there has to be a thought process behind doing so.4 An import tariff on a product that hasn’t been made in the United States for decades is not going to do anything except increase prices on consumers. Because, despite other rhetoric, importers absolutely pass the cost along. No one is absorbing a tariff, they are just calculating it into the final cost of the product before their markup. Goldman Sachs believes that for every percent increase in average tariff rate, consumer prices rise at least 0.1 percent. And Ronnie Robinson, chief supply chain officer at Designer Brands, says that for every dollar the government adds in tariffs, consumers generally pay an extra $2 to $4 at checkout.

In today’s economy, tariffs should be used as a method for protecting our own domestic production, not for penalizing anyone. That’s why Trump implemented tariffs on Chinese-made steel – the U.S. has a steel industry, which needed governmental support to stop the bleeding of production being outsourced. Biden wants the eco-revolution to take place here, not overseas – which is why he wants solar panels and electric vehicle batteries manufactured here. But if something is not already made here in the quantity needed to meet demand, a tariff is just a consumer tax. That’s where a tariff on all imports can be extremely harmful to our country.

But none of us get to make these policy decisions, of course. Let’s say the next president decides to implement a ten percent tariff on all imported goods. Are you prepared for how that will affect your business?5

If you’re in a service business that doesn’t use any raw materials or sell any goods, you likely wouldn’t be affected by tariffs. But most businesses, at some level, need to purchase goods. Whether the tariff would affect the good itself, or the raw material that helped make it, at some point through the supply chain, unless it was fully sourced from the U.S., it will cost ten percent more. No business is absorbing that cost – but can it be passed onto consumers without stifling demand?

Unlikely. More likely is that consumers will find a way to purchase the product from the original source overseas, bypassing CBP directly. You see, any shipment valued under $800 is not required to clear U.S. Customs – that’s why, when you order a $25 item from Alibaba, it comes right to your door without you needing to argue with a CBP agent. But companies need to import shipments in bulk quantities – on pallets, in containers, etc. The customs costs associated with that, as well as any new tariff, goes right into the cost of a product. If an item that cost $10 from the manufacturer now costs $20 after all of the import fees and tariffs, the selling price to the consumer will also double. But if the consumer can buy it from China themselves for $20, plus a few dollars in shipping, they’ve now bypassed the American economy completely. In this situation, a tariff, initially implemented to protect American companies, has in actuality moved consumer business outside of our borders. Let’s not forget to mention that, if a 60 percent tariff is implemented on Chinese goods, most companies will simply stop importing those goods completely, thereby harming their entire business if there is no domestic replacement. That, too, would harm the American economy much more than the Chinese economy.

Unfortunately, there is no all-encompassing answer to how you can protect yourself from these scenarios. None of us know who will win in November. And none of us know exactly what trade policies the next president will implement, if any. But as business owners, our job is to be prepared for what is coming down the pike. If what’s coming is more tariffs, be sure you have a deep understanding of how it will affect your business, as well as a few strategies for how you can overcome them.

Custom House bosses would pocket up to $50,000 per year extra from this skimming, equivalent to over $1 million today. And it was totally legal.

For more fascinating information, go grab that Chester Arthur biography off your bookshelf. Wait, you don’t have a Chester Arthur biography like me? Hey, where’d everybody go?

Amazingly, New York Custom House existed until 2003, when CBP was established and took over all customs clearing duties – no pun intended.

One argument for a straight five percent tariff on all imported goods, with no difference based on commodity, is that customs clearing would be much simpler, lowering the labor cost to the government of collecting on tariffs and businesses on importing goods.

Trivia time: which country has the highest average tariff rate in the world? I didn’t expect it to be the Bahamas, at 18.6 percent, did you? Gabon is second at 16.9.