How to Overcome Imposter Syndrome

Humility is of utmost importance when leading a company. But what if your self-esteem is on the other, lower end of the spectrum?

**Note: If you missed my newsletter on humility, I highly recommend going back to read it, as it segues directly into today’s**

A few weeks ago, I wrote about the importance of having humility as a business leader. But what if you fall on the other end of the spectrum? Not every person is confident or has a great sense of self-worth. All of us have, at some point, interacted with someone who was great at their job, but they didn’t quite realize it. A colleague makes a small error, and then it snowballs as they spiral into an emotional purgatory. Sometimes an employee isn’t willing to work on a challenging task because they don’t think they’re capable of completing it. Perhaps even some of us have, at times, wondered if we were truly fit to be in our current positions.

There’s actually a psychological term for this: imposter syndrome. Originally coined in the late 1970s as “impostor phenomenon” by Pauline Rose Clance and Suzanna Ament Imes, their research followed high-achieving women and how they viewed their own success. They found that there were an inordinate number of these women who felt they were not truly intelligent: their success was only due to luck; or they were only admitted to higher education because of errors in the admissions process. Clance and Imes dug a bit deeper and suggested that some of imposter syndrome could come from how they were raised. For example, if a set of parents constantly told a child they were the smartest, best person, better than anyone around them, that child, when fully grown, would be less likely to be able to handle adversity if it arose.1

Now, in fairness, even forty-plus years later, scientists still don’t know exactly where imposter syndrome comes from – Clance and Imes simply published a theory that continues to be tested to this day. But what is irrefutable is that imposter syndrome is real. It’s been found again and again, both in scientific research and in the working world. It even goes back to Shakespeare’s days, where The Bard famously wrote, “Our doubts are traitors, and make us lose the good we oft might win by fearing to attempt.”

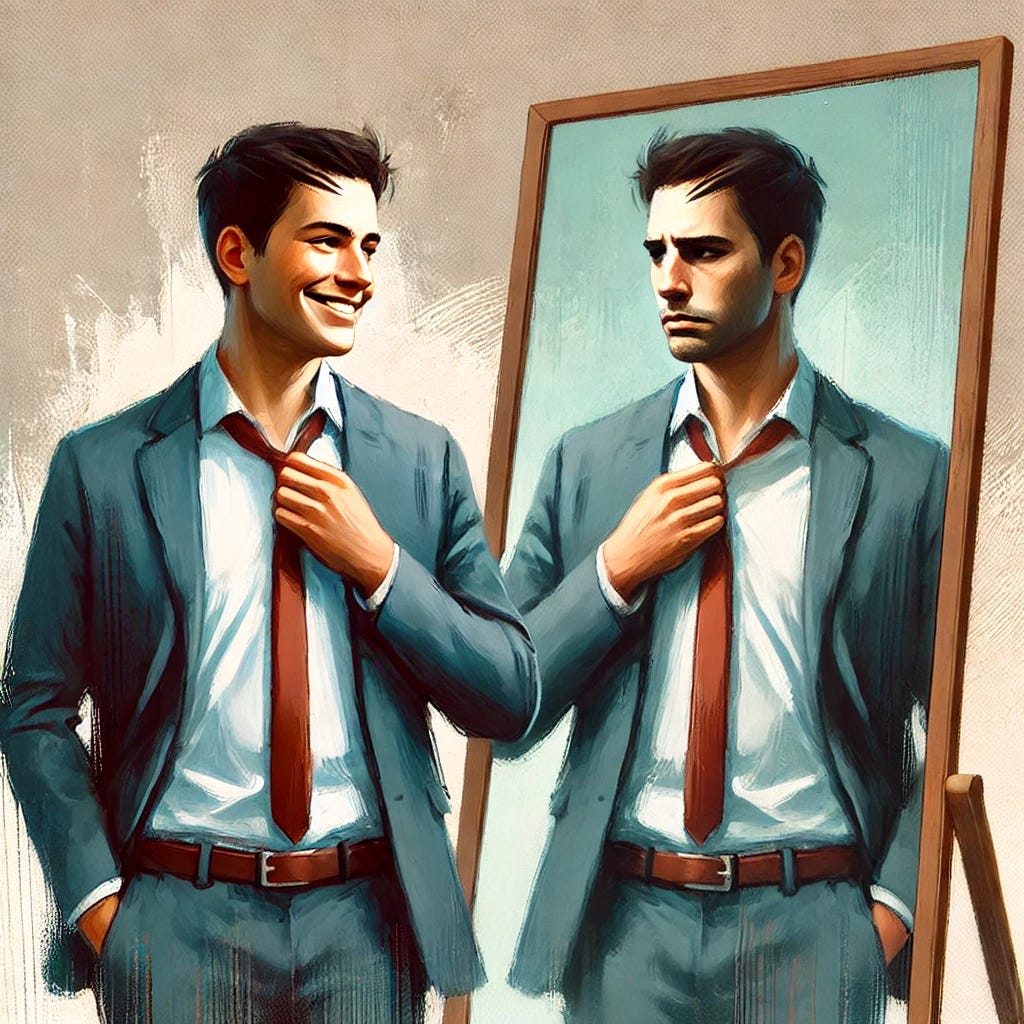

Source: ChatGPT prompt for “imposter syndrome, painterly style”

Time to spew some data: one study found that 85% of people sometimes feel inadequate or incompetent at work, but only 25% are aware of the term “imposter syndrome.” Another study shows that 78% of business leaders have experienced imposter syndrome, and 59% of those have considered leaving their role because of it. And another survey found that women are twice as likely to suffer from imposter syndrome than men, whereas millennials are the age group most likely to have these feelings of self-doubt. Imposter syndrome is even linked to burnout in medical students, but recognizing it and knowing how to combat it is linked to resiliency.

These feelings can have incredible negative consequences, both for someone’s career and their mental health. Some people with imposter syndrome fear they will be “found out” for their perceived incompetence and punished accordingly, either with a loss of position, embarrassment, or full on failure. While not an actual medical or psychological diagnosis, imposter syndrome is a real issue that millions of people deal with on a regular basis, none more so than some small business owners. People suffering from imposter syndrome will often see their emotions snowball after making a small mistake, saying the wrong thing in a meeting, etc. It gets even worse when someone is prone to anxiety or depression – and all of us experience peaks of anxiety, whether you know it or not.

Most of us believe that others think about us much more often than they actually do. We especially tend to believe others are judging us much more often than they actually are. In actuality, people generally just think about themselves most of the time.

Imposter syndrome is most prevalent in people who have big ideas and big ambitions. Any high-achiever, basically. I’ll give you a great, obvious example: this newsletter! When I first mentioned to my wife that I wanted to get back into writing, but didn’t have any specific ideas, we started discussing how to combine my love of psychology and business.2 When the idea arose to start a weekly newsletter about business leadership, I believe my actual words were, “Who am I to lecture anyone about business?” Fast forward through a hefty bit of back-and-forth dialogue where she convinced me that I actually was qualified to do this, and we ended up here at Main Street Mindset.

There are also many times that I need to be slapped around by a colleague, a business partner, a family member, or friend, when I mention that I had nothing to do with a particular piece of business success. I am admittedly humble and always like to give credit first to my staff, who do most of the work (just like in most businesses). But there’s a fine line between humility and imposter syndrome. I always have incredible pride in my companies, but I do often have to stop and recognize when I did something well, to avoid falling into that trap. In fact, it’s slightly painful to even type the words “I did something well,” because, well, that whole humility thing that I was raised with. But I have been fortunate to rarely feel that I am incompetent or a “fraud” at work. There are always things I need to improve upon, but I generally feel confident about my ability to perform.

One way of avoiding imposter syndrome is to define “success” at any given moment. My bar for success moves regularly, depending on how things are going. If it’s been a terrible week at work (we all know what those are like), perhaps “success” for me is just surviving the day in one piece and getting home. If it’s been a good week, maybe the bar is much higher, and I have to work even harder to achieve it. Not sticking to one static judgment of what constitutes “success” is an easy way to ensure that you are feeling able to do your job and lead others simultaneously.

When you begin to feel imposter syndrome, another great fix is to steer into it – if you truly feel you’re not smart enough or capable of doing something, stop and ask yourself why you think that, and what you can do to make yourself more capable. Do you need to do some Google research? Watch a YouTube video? Ask a mentor for help? Read a book? Get more formal education? More often than not, you’ll find you’re perfectly capable – and if you’re legitimately not, then at least you have a plan for how to become so.

But perhaps the best explanation on how to overcome imposter syndrome comes from Randall Nedegaard, a California State University researcher. He writes:

“Feeling like an imposter when we start something new appears to be a fairly common experience. My conversations with colleagues throughout the years suggest that when we are thrust into new situations where there appears to be little room for error, our insecurities can really be triggered. The path to overcoming these feelings seems to involve at least two important factors. First, we have to have an openness to feedback we get from those we are working with. … But evaluations and feedback can create feelings of vulnerability. Therefore, the second important factor is having the confidence and/or courage to embrace vulnerability.”

You can easily see how “having humility” and “avoiding imposter syndrome” can feel almost impossible, since they are nearly opposite one another. You have to be proud of your work and confident that you can handle it. But not TOO confident. You have to keep remembering how smart you are. Wait, not THAT smart!

The logic behind balancing these two psychological phenomena is quite circular and very difficult to follow at times. You need to have confidence, while not allowing that confidence to turn into arrogance. You need to recognize you’re capable, but not show off to others just how capable you are. You need to believe you can handle anything thrown your way, but handle those curveballs quietly and effectively. It’s a delicate line to straddle, but if you can do so, you’ll set yourself up for success, not just in business, but in your everyday roles as well.

If I wanted to go on a tangent, this would also segue nicely into Carol Dweck’s research on growth mindset. In short, Dweck focuses on the importance of believing that our intelligence and abilities are able to be improved in life. People that believe their intelligence is fixed for life perform much worse than those who believe it is malleable.

Plenty of people said, “Why don’t you write another book?” When I responded with, “Okay, about what,” most people quickly backed off. Pro tip: you generally need to have a passionate idea about something before you can even consider writing a book about it.