Employees say they’re motivated by more money. The data disagrees.

Handling this difficult issue is one of the biggest challenges you will face as a business owner.

As business owners, one of the most difficult subjects to deal with is compensation, especially when an employee states (either to you or their coworkers) that it’s the motivating factor behind their attitude at work. We’ve all likely been there at least once, if not multiple times. That’s a universal desire in the working world, whether it’s a stated priority or not.

How many times have you heard of someone saying they would work harder if they were paid more? The problem is, even if you were to give everyone a 20 percent raise, all of the data available shows that, despite what people say, it will not actually increase their motivation or their engagement. It may give them a temporary burst of happiness – but after some period of time, their emotional state will likely return to where it was before the increase.

Gallup’s State of the Global Workplace report shows that a majority of the U.S. workforce is not engaged with their jobs. But money and compensation have been shown to have an effect on workers only to the point that they need to have a comfortable living wage. This has been found as far back as 1959, when Frederick Herzberg published a study that found salary can prevent dissatisfaction, but does not alter job satisfaction or motivation. This makes perfect sense. Put yourself in their shoes: as an employee, you're going to be annoyed if you're making less than you're worth, but a raise isn't going to stop you from dreading going to work everyday when Greg from accounting keeps spouting those horrible financial puns to you with an obnoxious snicker.1

More recently, the famous psychologist Daniel Kahneman and economist Angus Deaton found in a 2010 study that emotional well-being improves only up to about $75,000 per year of salary. After that, happiness is not correlated with additional income. The impact of increased salary is also logarithmic – meaning if you take a high-income and a low-income person and increase each of their salaries by $1,000, the low-income person will see a greater increase in their life evaluation, as would be expected. But if you double both of their salaries, the change in their life evaluation is the same. This also tracks – $1,000 makes an enormous difference to someone who has to scrape every penny to feed their children. Someone making $200,000 would certainly like an extra $1,000, but it’s not going to change their world. Going to $400,000 overnight though? Watch out, Bezos.

But we still end up at the same end result. If you dread going to work every day, suddenly making double isn’t actually going to make you dread it any less, even if your lifestyle has improved. So, if money doesn’t actually make people more engaged with their jobs, what does?

Kahneman and Deaton found that people with higher income generally rated their life evaluation higher, but their daily emotions were not significantly different. “More money does not necessarily buy more happiness,” they write, “But less money is associated with emotional pain.” Income correlates with life evaluation, but the items that correlate with daily emotions are health, loneliness, and care-giving. In fact, they found that the value of a strong marriage is about $100,000 in annual salary. Meaning that if you take a (happily) married household with $100,000 of total income and compare it to a (lonely) single person making $200,000 per year, their happiness levels, on average, will be about the same. Money helps you live easier. It prevents negative emotions related to your ability to live comfortably. But having more of it doesn’t specifically make you happy.

Over the last few decades, there has been an inordinate amount of research about workplaces and employee motivation, and most of them have similar findings: people are, in reality, motivated by the challenges of their job, the culture of their job, the leadership at their job, and the purpose in their job. They want to be challenged so that their skills improve and they become proficient at certain tasks. They want to work at a place in which the culture is healthy and nurtures their growth. They want managers and leaders who follow their own rules and treat those around them with respect. And most importantly, they want to feel that what they do has a purpose.

Psychologically, motivation is divided into two categories: extrinsic and intrinsic. Extrinsic factors are “rewards” of sorts: money, recognition, promotion, etc. Intrinsic factors are internal: the desire to improve yourself, wanting to master a skill, feeling as if what you do matters. All of the items in the previous paragraph are intrinsic motivators. Extrinsic motivators are still important, because after all, it is a job, not charity. But they cannot be the determining factors for enjoyment and engagement.

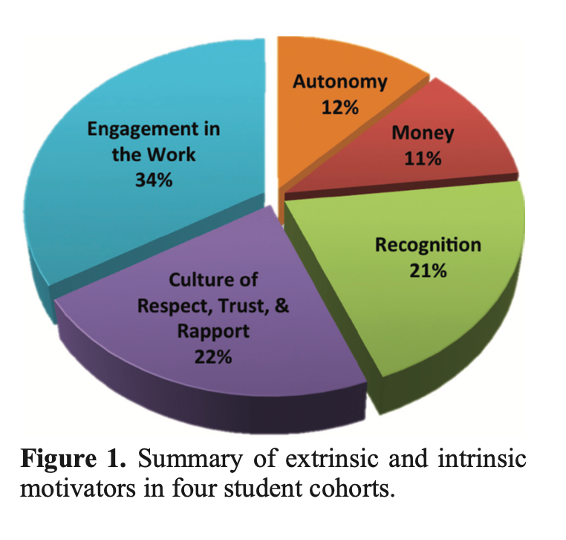

Psychologist Edward Deci, one of the fathers of motivation research, established in the 1970s that there are three parts of intrinsic motivation that are critical: autonomy, mastery/competence, and purpose. A 2016 study also found this to be the case, as is shown in the below chart. Only 11 percent of respondents said that money was the deciding factor in their motivation at work.

A separate 2016 study by Gallup has supported this idea, showing that employees who are more engaged but lower-compensated are often more satisfied and motivated in their job than those who are highly-paid but disengaged. I can list numerous friends and colleagues off the top of my head who took a pay cut to leave a stressful or unenjoyable job, and ended up being happier in the long run, despite the decrease in salary. Most of you probably know a few people like this as well.

The problem with a lot of this research is that most studies, by nature, are done either on college campuses or among workers of white collar industries, where starting pay is generally much higher and stabler than in the average job. College students are statistically from higher-income households, which means they would be less motivated by money, since they are not living paycheck to paycheck. It’s difficult to generalize those studies to lower-wage industries.

Nearly half of the workers in this country are in traditionally lower-wage industries like retail (9.4%), wholesale (3.5%), manufacturing (7.5%), warehousing and transportation (4.0%), health care (12.5%), and hospitality (9.6%). Most of these jobs have hourly wages, fringe benefits, and tireless hours. At the end of the day, when an employee complains about their rate of pay, you can’t just slap them in the face with a pile of research and tell them they’re wrong. You can’t just replace someone’s failure to pay their bills with purpose.

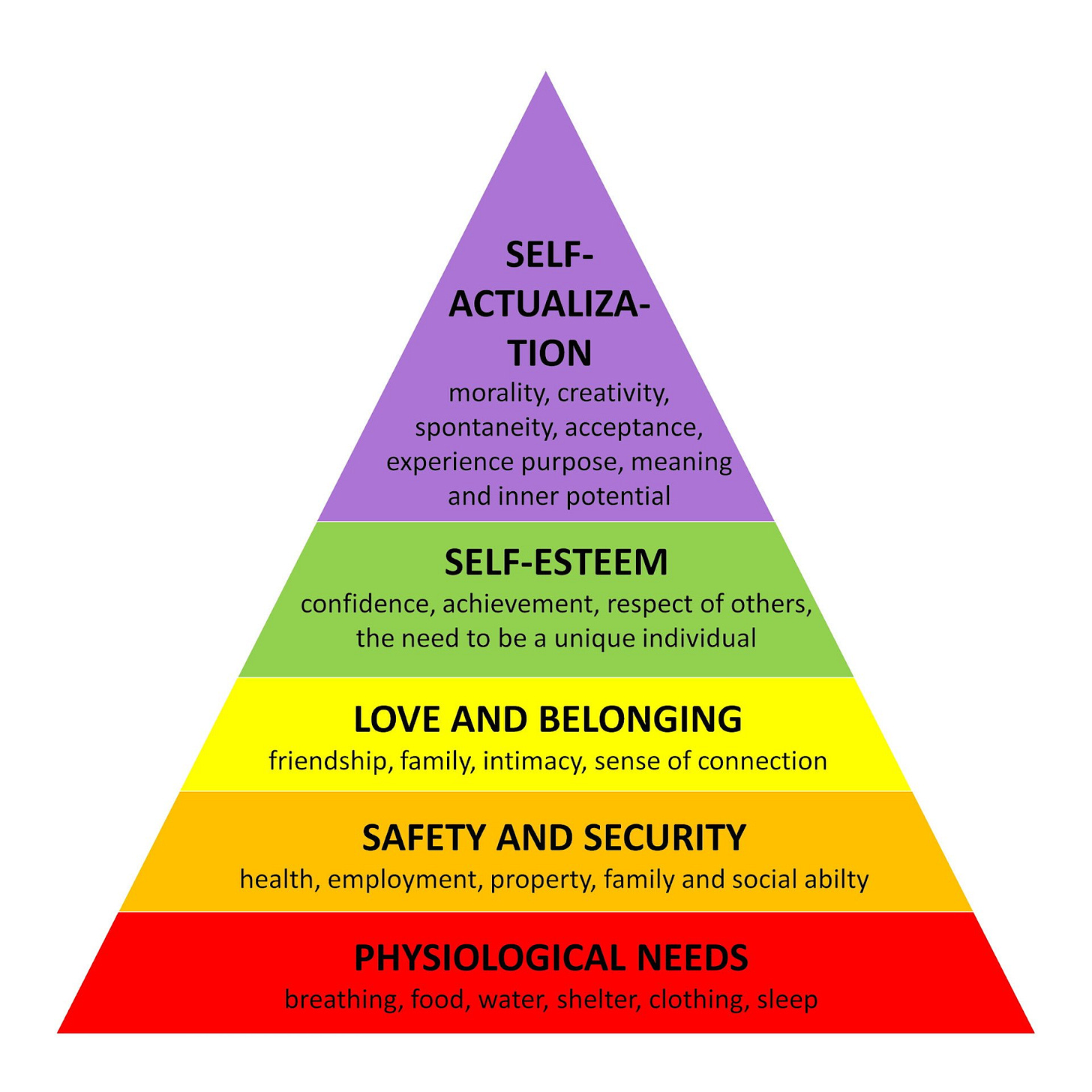

In fact, this idea has been around since 1943, when the legendary psychologist Abraham Maslow published his “Hierarchy of Needs” theory. His proposed pyramid has five levels, starting at the bottom. Each rung must be achieved in order to move to the next one, before ultimately reaching “self-actualization,” which Maslow states as our ultimate goal as human beings.

Most people have that bottom rung checked off (it was generally more relevant earlier in our evolution, when we were hunters and gatherers). The safety and security rung, though, is the one that is contingent on money. Note that, according to Maslow, the reward for becoming financially secure at this level is simply a move to the next rung. Self-actualization does not come until later in the pyramid.

This is supported in almost all subsequent research on the topics. Not having enough money to live is one of the major stressors in someone’s life. But once they have enough money to get by, it no longer affects their happiness. Which means that if you’re not paying your employees enough to get by in the first place, then it doesn’t matter how engaged you make them. If you are paying them enough, and they’re still disengaged, that means it’s a problem with your workplace – even if they claim it’s financially-driven.

Some employees will always be unhappy, no matter what you do. It happens. Everyone is different, and it is impossible to create a one-size-fits-all manual for engagement and motivation. But perhaps bestselling author Daniel Pink said it most eloquently: “The best use of money as a motivator is to pay people enough to take the issue of money off the table.” Hopefully you can afford to do that in your business.

Once you take care of the basic “money” issue, the onus is on you to make sure your workplace creates an atmosphere of engagement for everyone that walks through the door. That doesn’t mean every task has to be enthralling. But you can, by example, show the importance of the work being done, the meaning of it, the effect it has on others, and your care and passion for the job. That should at least be the start of a trickle-down effect on the rest of your staff.

I might be Greg from accounting.