Do You Have the Right Mindset For Managing People – Or Yourself?

Psychologist Carol Dweck has spent her life researching mindsets that push people to succeed. The U.S. Army uses it. Why don’t more businesses?

Anytime that we’re hiring, I tend to browse job postings in my area just to see what potential recruits will see. To me, it’s a great way to keep on top of our local region, as well as ensuring that our job offer is on (or above) par with other businesses competing for talent. Inevitably, I find the same thing that’s been complained about ad nauseum over the last few years: tons of positions for entry-level jobs that require a ridiculous amount of experience. That’s kind of oxymoronic, isn’t it? The definition of entry-level is the lowest level in a company’s hierarchy. If it’s the lowest level, why do you need experience? And if you have experience, why would you be looking for an entry-level job?

My basic hiring philosophy came from my years of studying psychology in school and the post-years, where I’ve tried to keep up on the biggest theories and researchers in the field (as well as some familial history, which we’ll get to). One of these researchers is Carol Dweck, a Stanford professor and winner of multiple science awards over the years. Her fantastic book, Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, came out in 2006, but I had been familiarizing myself with her research before she published it.

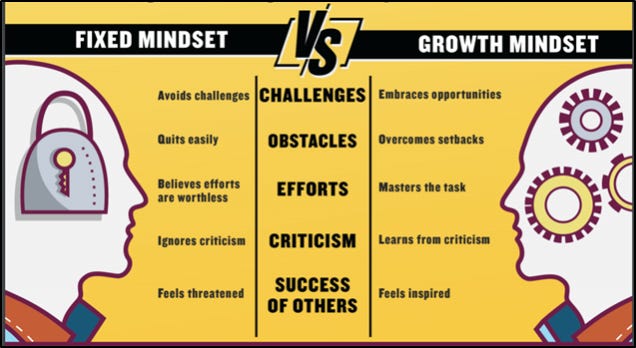

Dweck’s research found that there are two kinds of mindsets among people: fixed and growth. To boil it down quite simply, people with a fixed mindset believe someone’s intelligence is fixed – you’re born with it and you cannot improve it, no matter how hard you try. A growth mindset means you believe that your intelligence is malleable, and you can improve it with deliberate effort.

Now, it doesn’t take a genius to guess that it’s better to have a growth mindset, but the research goes much deeper than that. Fixed mindset people tend to learn with the goal of looking smart (because remember, they don’t believe they can actually improve upon themselves. They are what they are). These people are often afraid to challenge themselves or take risks, because failure suggests a lack of intelligence. They don’t want to look “stupid” in front of others, or even to themselves. Growth mindset people, on the other hand, tend to continuously seek out challenges, because even if they fail, they understand that the experience can help them improve upon themselves for the next time.

Dweck’s research career started with a basic question: “What makes a really capable child give up in the face of failure, where other children may be motivated by the failure”? That question can be asked about adults in the working world as well. The difference between the two mindsets can be seen in two people working on the same, difficult task. One person says, “I’ll never figure this out.” The other one says, “Okay, let’s try this again.” Most importantly, if you don’t have a growth mindset, you can develop one. You can have a growth mindset about growth mindset!1 All it takes is the understanding that you can always improve upon yourself, and you’re on the right track.

But as obvious as this is, our society as a whole seems to refuse to act accordingly, even if we think we are. How often do we see a child struggling with a subject – let’s say a young girl in math class – and say things like, “Oh, she just doesn’t have the brain for math,” or “Well, I know girls aren’t as good at math as boys.” The math children are doing at that age? There’s no innate talent for it. Perhaps I’ll buy the theory if you tell me your kid doesn’t have a brain for AP Calculus when they’re 18 years old. But basic addition? Subtraction? Multiplication tables? Everyone has the capability to learn those skills. By making excuses for them, we are essentially telling them they have no chance to improve their intelligence. What kind of a lesson is that?

So, when we’re hiring for basic or entry-level jobs, why are we so focused on traits that are irrelevant? If I’m hiring someone to work in our office, why would I care if they have previous office experience? Why do I care if they’ve used our specific software before? The only thing I truly care about is if they have the ability and the mindset to learn and grow. No employee, no matter how experienced, comes into your organization ready to hit the ground running, with no training necessary. It’s impossible – every company has their own structure, their own process, their own operational strategy. Even the smartest, most brilliant person needs time to learn that.

The U.S. Army is one of the greatest examples of this. Think about what a private will have to achieve one day: they will have to get in incredible shape. They will have to learn to shoot a weapon accurately. They will have to learn how to read a situation on a battlefield and make life-or-death decisions. It is perhaps one of the most consequential jobs one could have in their life. And yet, does the Army say, “Sorry, we don’t want you, we’re really looking for someone with more experience at wartime strategy”? Of course not, that’s ridiculous. Instead, the Army firmly believes that they can take anyone physically and mentally willing and turn them into an excellent soldier. In fact, they’ve taken Dweck’s research and turned it into a chart for recruits so they know what is expected of them:

The Army talks about the “power of yet.” A recruit never says “I can’t do X.” They say, “I can’t do X yet.” The organizational structure imbues their recruits with the knowledge that it’s only a matter of time before they learn it, because anyone can learn anything.

In fact, our basic hiring practice stems not only from this idea of growth mindset, but from a strategy that came from my grandfather (who was hiring people well before Dweck did her research). He would write a string of random letters and numbers, and ask people to put it in alphabetical and numerical order. If they could do it, he figured they were “smart enough.” Everything else past that could be learned. Our HR manager does something similar today – are you smart enough to work here?2 And do we believe you have the capability and mindset to learn anything past that? Great, you’re hired. It doesn’t always work out, don’t get me wrong. We have our hiring snafus, just like everyone. But as a whole, it makes the process much easier. We don’t care much about experience, how long they held their last job, or any other pointless trait. We just want to know if they are willing and able to learn.

Employing a growth mindset has shown to be incredibly valuable to an organization. “When entire companies embrace a growth mindset, their employees report feeling far more empowered and committed,” writes Harvard Business Review.

“They also receive greater organizational support for collaboration and innovation. In contrast, people at primarily fixed-mindset companies report more cheating and deception among employees.”

Enron is an extreme example of how a fixed mindset can doom a company. Mistakes were seen as failures at Enron, and were not acceptable. At one point, the company was a legitimate, profitable firm. But as their debt skyrocketed and financial errors were made, people covered them up instead of telling their superiors. That culture eventually permeated the entire company, snowballing into what was eventually a complete fraud.

Enron also had an infamous “rank and yank” policy, where every employee in the company was ranked each year, and the bottom 15% were automatically fired. This certainly doesn’t encourage people to learn and improve; it creates fear, anxiety, and paralysis.

The popular idea is that greatness is born, not made. This is especially apparent in sports, where people talk about natural, God-given talent. There are certainly genes and traits that make someone predisposed to be successful athletically, but there are almost no examples of someone succeeding without going through years of hard work. If the best athlete at age 11 believes they’re born with all the talent they’re going to have, that child is going to be passed quickly by those that believe they can improve.

Growth mindset is not limited to just hiring. It can be extrapolated to an organization’s hierarchy, structure, and operation – as well as your own mindset as a leader. When someone makes a mistake, do you automatically criticize them? If so, what is the rationale behind the critique? Mistakes are bound to happen, and criticism is needed in many scenarios. But you don’t want to criticize the mistake itself. You want to find the reason for the mistake, and see if that warrants a proper chiding. Was it that the person didn’t give the proper effort? Did they not understand the training properly and fail to ask for clarification? Were they afraid to ask for help, so instead they guessed?

I don’t have data on this, but I believe the critique I level most often at my staff is, “Why didn’t you ask for help?” I certainly encourage them to have autonomy over their job. But I also tell them to ask questions. If someone fails to do that, that’s a valid critique. You’re not mad at the fact that they made a mistake; you’re mad at them not taking the proper effort to ensure it was being done correctly when they were unsure. Similarly, if you praise someone, don’t tell them how smart they are or how talented they are. Praise something specific: “I really loved how you looked at that problem from a few different angles before making your ultimate decision,” or “You worked really efficiently to ensure that it got done on time.” Most importantly, you don’t ever want to just praise effort, especially if the effort was misguided. Outcomes still matter in business. You want to praise concerted effort that resulted in learning and understanding. Someone may have tried incredibly hard, yet still made a mistake; but if they haven’t learned how to improve for next time, the effort was for naught.

Does your company encourage people to have a growth mindset? Or do you expect people to walk in on day one and be proficient? Do you give them the space and the tools to improve? Or do you expect it to happen by osmosis? The answer to these questions will tell you whether you have a company culture that sets its people up for success and longevity.

So meta.

And the bar isn’t very high – for Pete’s sake, I run the company.